The idea that the Sun is a star, just like the tiny specks we see in the night sky, originates, like many things, in ancient Greece. The first mention comes from around 450 BC and is attributed to the Klazomenian philosopher Anaxagoras. But it would take a couple of millennia and the insights of figures such as Galileo and Newton (and many others) before the German scholar Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel would lay the foundation of a more solid proof.

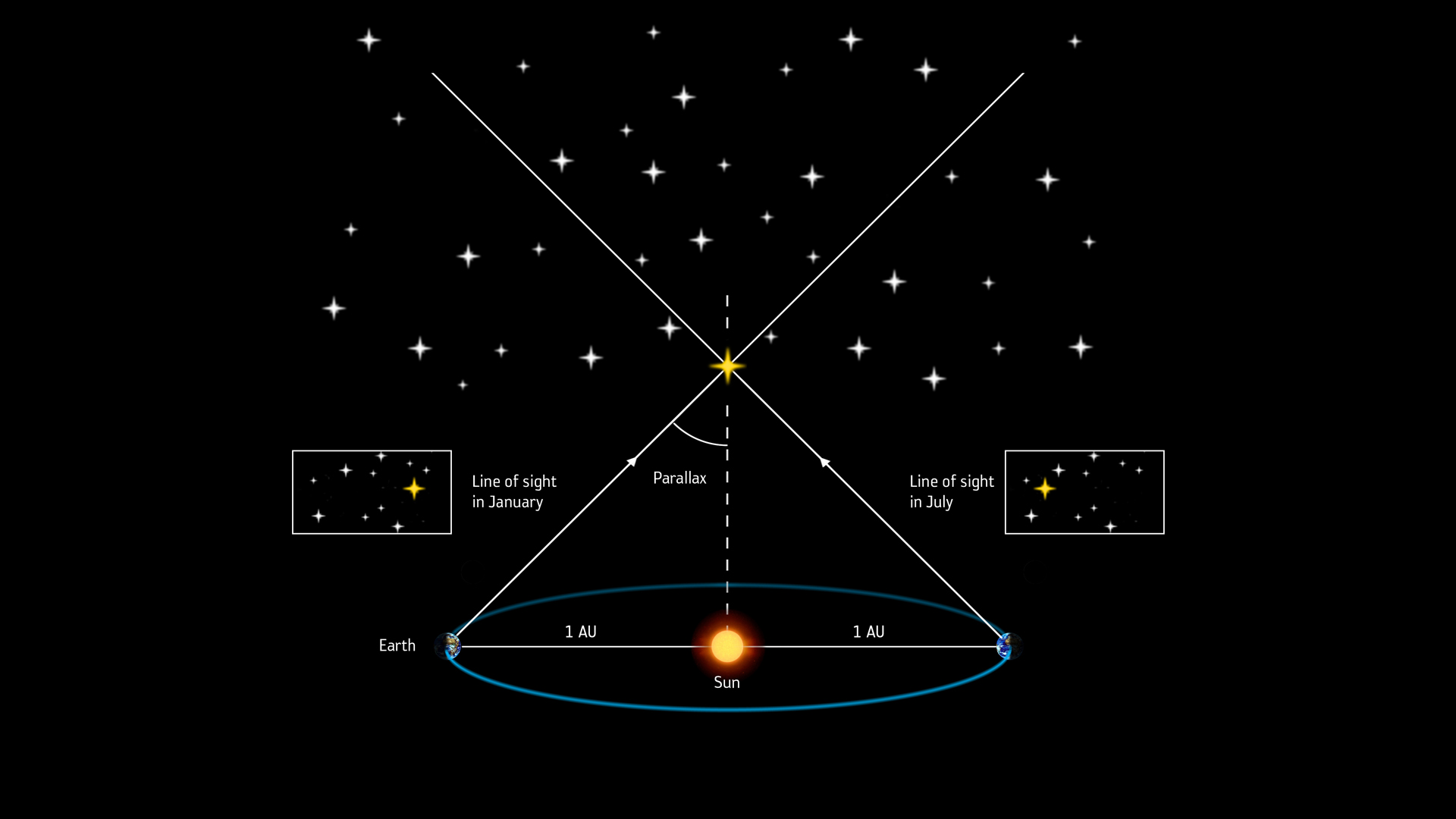

This astronomer, born in 1784, was the first to accurately measure how far nearby (we’re still talking lightyears) stars are. Try holding your thumb in front of your eyes. Now close one eye, then the other: your thumb appears to be moving! The angle by which it shifts (or more precisely, half of that angle) is called parallax. In astronomy, you compare the star you’re observing to the distant ones that don’t seem to move at all. Instead of closing one eye and then the second, astronomers take two measurements 6 months apart.

And here comes the part physicists love: since the distances are so vast and the angles so tiny, we can model the Earth, Sun, and the star as forming a right triangle, with the right angle at the Sun. In such a triangle, the tangent of the angle is defined as the ratio of the opposite side to the adjacent side, giving us: $\tan\left(p\right) = \frac{a}{d}$, where $a$ is the distance from the Sun to Earth and $d$ denotes how far is the star we are measuring.

But we have more tricks up our sleeve. Just like we use meters on Earth, astronomers like to use a unit called the astronomical unit (au), defined as the average distance from the Earth to the Sun. That means $a=1$ au. Furthermore, since we’re dealing with minuscule angles, we can approximate $\tan (p)\approx p$ (If you don't believe me, try plotting $f(x)=\tan\left(x\right)$ and $f(x)=x$. You can see that for small values of x, the graphs look very similar.). This simplifies our equation to $p=1/d$. In addition, you may have heard of parsec. That's the distance to an object whose parallax angle would be 1 arcsec, or in other words 1/129600 of a full turn.

Now how is this connected to exoplanets (the hidden worlds I keep hinting at)? Well, Bessel's calculations revealed that the universe is absolutely massive. Moreover, by measuring how far stars are and how bright they appear, we can calculate how luminous they actually are and how that compares to the Sun. Thanks to the work of Bessel and astronomers after him, one could presume that the Sun is not unique. And since the ancient Greeks already knew about planets (more or less), it is easy to hypothesise that every star could have some objects orbiting around it…

Sources: Friedrich Bessel and the Companion of Sirius. American Museum of Natural History [online]. 2000 [cit. 2025-07-12]. Available at:

https://www.amnh.org/learn-teach/curriculum-collections/cosmic-horizons-book/friedrich-bessel-sirius-b

A history of astrometry - Part II Telescope ignites the race to measure stellar distances. ESA [online]. 2000 [cit. 2025-07-12]. Available at:

https://sci.esa.int/web/gaia/-/53197-seeing-and-measuring-farther